On August 14, a devastating magnitude 7.2 earthquake hit Nippes, Haiti, causing thousands of deaths and widespread damage to homes, churches, schools, and other infrastructure. In the midst of this humanitarian crisis, geoscientists are working to understand exactly what happened on the fault (or faults) responsible—which is critical to understanding future risk.

One piece of that work is a project led by Eric Calais, Professor at Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris and in residence at Université d’État d’Haïti, and Steeve Symithe, Assistant Professor at Université d’État d’Haïti and former COCONet Science Fellow. UNAVCO engineers worked hard to quickly prepare 10 field GPS kits from the GAGE Facility equipment pool and ship them to the team in Haiti. These self-contained kits—weatherproof cases containing GPS receivers, antennas, mounts, batteries, and solar panels—will be used to accurately measure the current position of many existing benchmarks that likely moved during the earthquake.

At the same time, replacement components for two permanent GPS stations in Haiti—both part of the Network of the Americas—were prepped and shipped so the team could bring them back online. Station JME2 in was the closest to the earthquake, just 100 kilometers away in Jacmel, but it lost communications last year. If the GPS receiver is functioning, the team may be able to download valuable data from the earthquake. [Update: they were successful!]

Station CN09 was a little farther away in Cap-Haitian. Unfortunately, it had previously lost its power source, so won’t have any recent data. With the addition of solar panels and batteries (and anything else it might need), Dr. Calais and Dr. Symithe will be able to get this station contributing again.

Two pallets of field GPS kits and permanent station components, ready to ship. (Photo: Annie Zaino)

UNAVCO Engineer Erika Schreiber packs a campaign kit. (Photo: Annie Zaino)

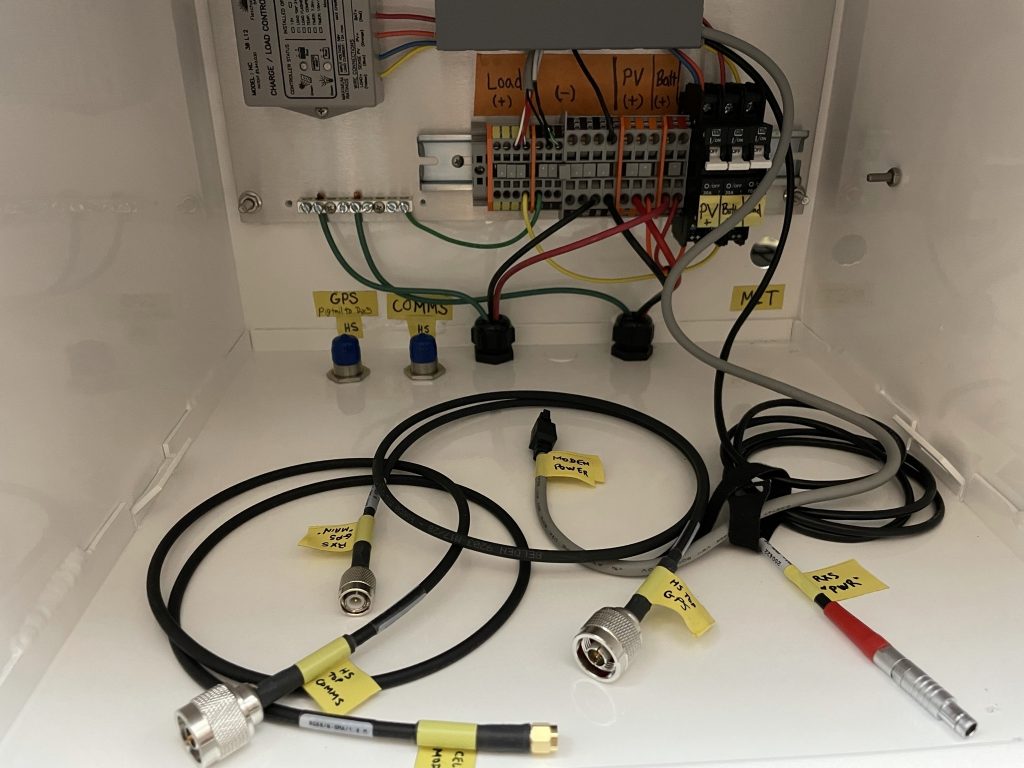

Cable management inside a permanent station. (Photo: Annie Zaino)

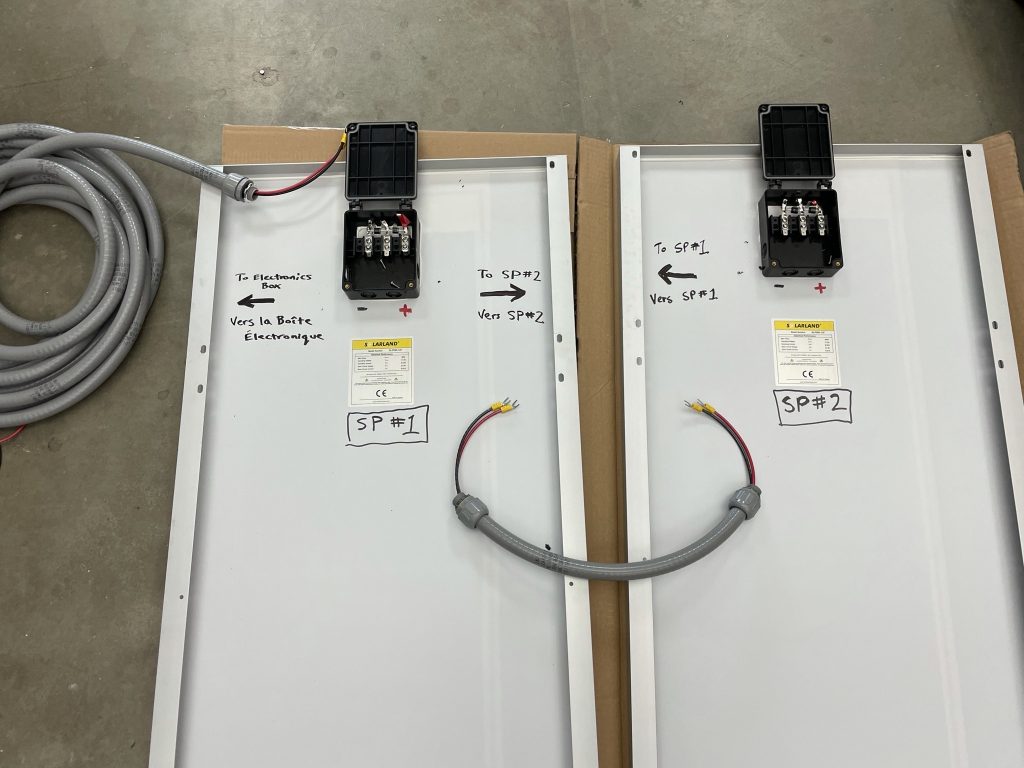

Permanent station components, ready for assembly. (Photo: Annie Zaino)

The earthquake occurred along a complex fault system known as the Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault zone and the rupture has been difficult to characterize from the available data. Satellite InSAR data, for example, have shown fault movement in the area, but it’s not completely clear which fault segments moved and by how much.

By resurveying benchmarks that may have moved as a result of the earthquake, the researchers will fill in gaps and map out fault movement. (Dr. Calais and Dr. Symithe have also been part of a study analyzing data from a network of inexpensive seismometers installed in homes across Haiti.) The better the fault movements are known, the better we can see how it affects other fault segments in the area. Slip on one segment of a fault can increase the strain on a neighboring locked segment, for example, or could reduce the force clamping another fault together. This information is important for estimating the future earthquake hazard—just as researchers did following the 2010 magnitude 7.0 earthquake, which occurred just to the east—and highlighting infrastructure at risk.

Because, ultimately, the goal of this science is to help protect people.

Written by:

- Scott K. Johnson and Annie Zaino

- Posted: 8 September 2021

- Last updated: 20 October 2021

- Tags: Haiti, project highlights